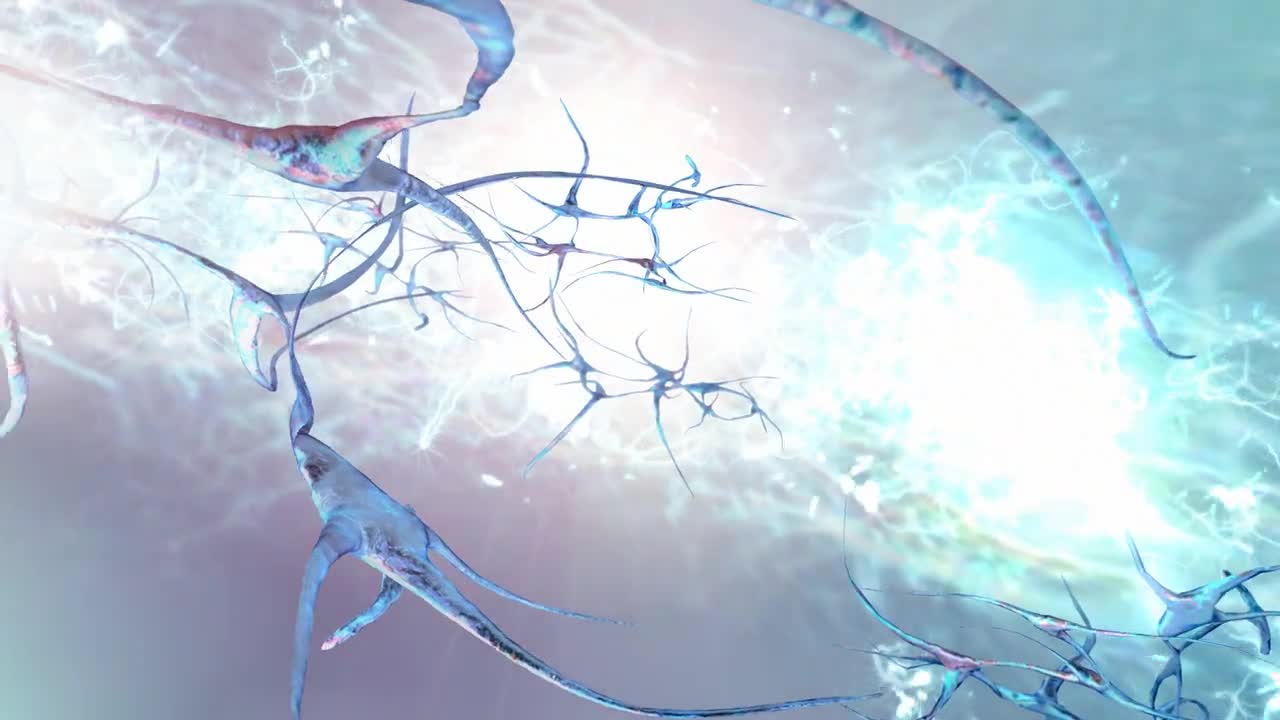

When people talk about consciousness, or the mind, it’s always a bit nebulous. Whether we create consciousness in our brains as a function of our neurons firing, or consciousness exists independently of us, there’s no universally accepted scientific explanation for where it comes from or where it lives. However, new research on the physics, anatomy, and geometry of consciousness has begun to reveal its possible form.

In other words, we may soon be able to identify a true architecture of consciousness.

The new work builds upon a theory Nobel Prize-winning physicist Roger Penrose, Ph.D., and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff, M.D., first posited in the 1990s: the Orchestrated Objective Reduction theory (Orch OR). Broadly, it claims that consciousness is a quantum process facilitated by microtubules in the brain’s nerve cells.

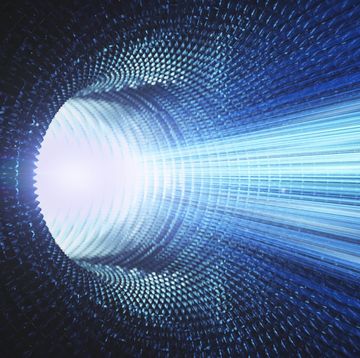

Penrose and Hameroff suggested that consciousness is a quantum wave that passes through these microtubules. And that, like every quantum wave, it has properties like superposition (the ability to be in many places at the same time) and entanglement (the potential for two particles that are very far away to be connected).

Plenty of experts have questioned the validity of the Orch OR theory. This is the story of the scientists working to revive it.

Across the Universe

To explain quantum consciousness, Hameroff recently told the TV program Closer To Truth that it must be scale invariant, like a fractal. A fractal is a never-ending pattern that can be very tiny or very huge, and still maintain the same properties at any scale. Normal states of consciousness might be what we consider quite ordinary—knowing you exist, for example. But when you have a heightened state of consciousness, it’s because you’re dealing with quantum-level consciousness that is capable of being in all places at the same time, he explains. That means your consciousness can connect or entangle with quantum particles outside of your brain—anywhere in the universe, theoretically.

Other scientists had an easy way to discard this theory. Efforts to recreate quantum coherence—keeping quantum particles as part of a wave instead of breaking down into discrete and measurable particles—only worked in very cold, controlled environments. Take quantum particles out of that environment and the wave broke down, leaving behind isolated particles. The brain isn’t cold and controlled; it’s quite warm and wet and mushy. Therefore, consciousness couldn’t remain in superposition in the brain, the thinking went. Particles in the brain couldn’t connect with the universe.

But then came discoveries in quantum biology. Turns out, living things use quantum properties even though they’re not cold and controlled.

Photosynthesis, for example, allows a plant to store the energy from a photon, or a quantum particle of light. The light hitting the plant causes the formation of something called an exciton, which carries the energy to where it can be stored in the plant’s reaction center. But to get to the reaction center, it has to navigate structures in the plant—sort of like navigating an unfamiliar neighborhood en route to a dentist appointment. In the end, the exciton must arrive before it burns up all of the energy it’s carrying. In order to find the correct path before the particle’s energy is used up, scientists now say the exciton uses the quantum property of superposition to try all possible paths simultaneously.

New evidence suggests microtubules in our brains may be even better at guarding this quantum coherence than chlorophyll. One of the scientists who worked with the Orch OR team, physicist and oncology professor Jack Tuszynski, Ph.D., recently conducted an experiment with a computational model of a microtubule. His team simulated shining a light into a microtubule, sort of like a photon sending an exciton through a plant structure. They were testing whether the energy transfer from light in the microtubule structure could remain coherent as it does in plant cells. The idea was that if the light lasted long enough before being emitted—a fraction of a second was enough—it indicated quantum coherence.

Specifically, Tuszynski’s team simulated sending tryptophan fluorescence, or ultraviolet light photons that are not visible to the human eye, into microtubules. In a recent interview, Tuszynski reports that, across 22 independent experiments, the excitations from the tryptophan created quantum reactions that lasted up to five nanoseconds. This is thousands of times longer than coherence would be expected to last in a microtubule. It’s also more than long enough to perform the biological functions required. “So we are actually confident that this process is longer lasting in tubulin than … in chlorophyll,” he says. The team published their findings in the journal ACS Central Science earlier this year.

Tuszynski notes that his team is not the only one sending light into microtubules. A team of professors at the University of Central Florida has been illuminating microtubules with visible light. In those experiments, Tuszynski says, they observed re-emission of this light over hundreds of milliseconds to seconds. “That’s the typical human response time to any sort of stimulus, visual or audio,” he explains. Shining the light into microtubules and measuring how long the microtubules take to emit that light “is a proxy for the stability of certain … postulated quantum states,” he says, “which is kind of key to the theory that these microtubules may be having coherent quantum superpositions that may be associated with mind or consciousness.” Put simply, the brain is not too warm or wet for consciousness to exist as a wave that connects with the universe.

While this is a long way from proving the Orch OR theory, it’s significant and promising data. Penrose and Hameroff continue to push the boundaries, partnering with people like spiritual leader Deepak Chopra to explore expressions of consciousness in the universe that they might be able to identify in the lab in their microtubule experiments. This sort of thing makes many scientists very uncomfortable.

Still, there are researchers exploring what the architecture of such a universal consciousness might look like. One of these ideas comes from the study of weather.

The Architecture of Universal Consciousness

Timothy Palmer, Ph.D., is a mathematical physicist at Oxford who specializes in chaos and climate. (He’s also a big fan of Roger Penrose.) Palmer believes the laws of physics must be fundamentally geometric. The Invariant Set Theory is his explanation of how the quantum world works. Among other things, it suggests that quantum consciousness is the result of the universe operating in a particular fractal geometry “state space.”

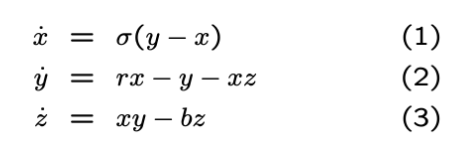

That’s a mouthful, but it roughly means we’re stuck in a lane or route of a cosmic fractal shape that is shared by other realities that are also stuck in their trajectories. This notion appears in the final chapter of Palmer’s book, The Primacy of Doubt, How the Science of Uncertainty Can Help Us Understand Our Chaotic World. In it, he suggests the possibility that our experience of free will—of having had the option to choose our lives, as well as our perception that there is a consciousness outside ourselves—is the result of awareness of other universes that share our state space. The idea starts with a special geometry called a Strange Attractor.

You may have heard of the Butterfly Effect, the idea that the flap of a butterfly’s wing in one part of the world could affect a hurricane in another part of the world. The term actually refers to a more complex concept developed by mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz in 1963. Lorenz was trying to simplify the equations used to predict how a particular climate condition might evolve. He narrowed it down to three differential equations that could be used to identify the “state space” of a particular weather system. For example, if you had a particular temperature, wind direction, and humidity level, what would happen next? He began to plot the trajectory of weather systems by plugging in different initial conditions into the equations.

He found that if initial conditions were different by even one one-hundredth of a percent, if the humidity was just a fraction higher, or the temperature a hair lower, the trajectories—what happens next—could be wildly different. In the graph, one trajectory might shoot off in one direction, forming loops and spins, seemingly at random, while another creates completely different shapes in the opposite direction. But once Lorenz started to plot them, he found that many of the trajectories wound up circulating within the boundaries of a particular geometric shape known as a strange attractor. It was as if they were cars on a track: the cars might go in any number of directions so long as they didn’t drive it the same way twice and they stayed on the track. The track was the butterfly-shaped Lorenz attractor.

Palmer believes that our universe may be just one trajectory, one car, on a cosmological state space like the Lorenz attractor. When we imagine “what if …?” scenarios, we’re actually getting information about versions of ourselves in other universes who are also navigating the same strange attractor—others’ “cars” on the track, he explains. This also accounts for our sense of consciousness, of free will, and of being connected with a greater universe.

“I would at least hypothesize that it may well be the case that it’s evolving on very special fractal subsets of all conceivable states in state space,” Palmer tells Popular Mechanics. If his ideas are correct, he says, “then we need to look at the structure of the universe on its very largest scales, because these attractors are really telling us about a kind of holistic geometry for the universe.”

Tuszynksi’s experiment and Palmer’s theory still don’t tell us what consciousness is, but perhaps they tell us where consciousness lives—what kind of a structure houses it. That means it’s not just an ethereal, disembodied concept. If consciousness is housed somewhere, even if that somewhere is a complicated state space, we can find it. And that’s a start.

Susan Lahey is a journalist and writer whose work has been published in numerous places in the U.S. and Europe. She's covered ocean wave energy and digital transformation; sustainable building and disaster recovery; healthcare in Burkina Faso and antibody design in Austin; the soul of AI and the inspiration of a Tewa sculptor working from a hogan near the foot of Taos Mountain. She lives in Porto, Portugal with a view of the sea.